TOC

Lately, I have been working on a pro-bono geology-focused data science project for a local consulting company here in Calgary. One of the most important things that I learned is how the division of a dataset in to training and test sets impacts model accuracy. Unfortunately I can’t share the results of project, so I’ll be demonstrating this concept with anonymized data.

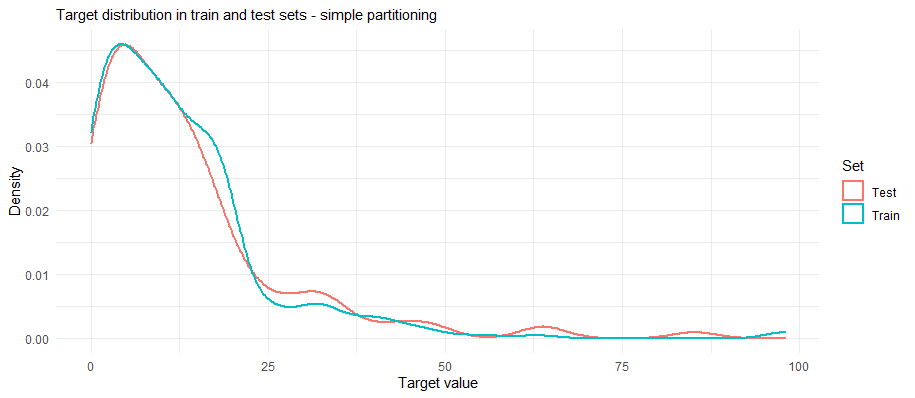

Throughout my learning (Coursera’s data science specialization and other reading) the partitioning of data into training and testing sets was a fairly minor part. Instructors/authors stressed getting similar distributions of target variables (values/categories you are trying to predict) in both the training and testing sets, however in almost all cases a simple data partition command was used:

createDataPartition() # in R’s caret

sklearn.model_selection.train_test_split() # in Python’s scikitlearn

These functions divide the dataset into based on the distribution of the target variable, so that the training and testing sets have similar distributions (see figure below). It was mentioned that in more advanced prediction other factors had to be considered (e.g., like the duration of time series signal used to train and the amount used to test).

When I started this project, I used a simple data partition and was excited about how well my models were doing. Little did I know I was giving the models a practice test that was very similar to the final exam.

Generalized Project

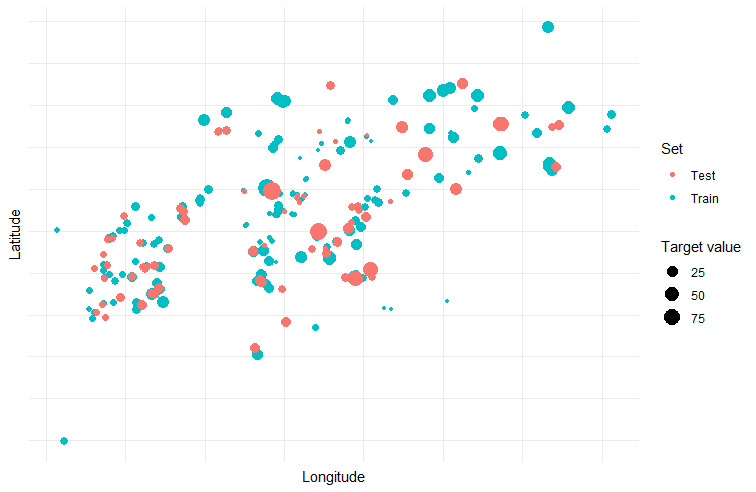

In this project, I’ve been tasked with predicting a geochemical property [y] from additional geochemical constraints [x1, x2, … xn] that have been sampled from subsurface horizons. This means that the sample locations have a spatial component, consisting of borehole locations (x,y) and depth (z). After working on the project for a week I asked a friend about assessing model accuracy. In response he asked me:

- how did I account for spatial the auto-correlation of the dataset? As rocks that are closer together are likely more similar than rocks that are further apart.

- were there were multiple observations from one well at different depths?

- how do sample geochemical properties vary across sample date, or from different labs?

- what are the impacts of these sorts of issues on model performance?

I realized that my simple data partition divided the dataset based on the target variable and in some cases had placed data from the same well (at different depths) or data from neighboring wells (at similar depths) into the training and testing sets. This may have allowed the model to be tested on data that was a bit too similar to the training data and inflated the accuracy.

Stronger Data Partitioning

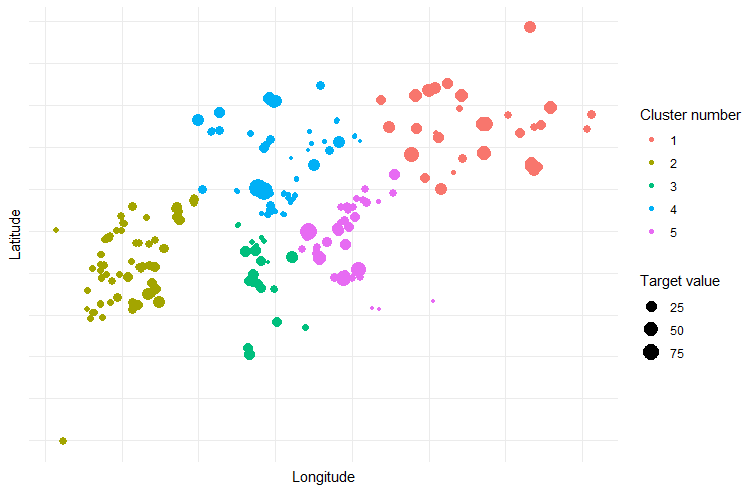

Based on this chat, I design two functions that would partition data in a more rigorous way. The first (enhanced partitioning) randomly selects wells and places them into either the training or testing until the desired proportion is reached. All records associated with each well are moved together. This testing scenario simulates the deployment scenario where you are filling in small portions of the area.

The second method spatially clusters the wells using k-means into an optimal number of clusters (decided by elbow method). The records associated with each cluster are added to the training data from smallest cluster to largest cluster until the desired train/test proportion is met. This partitioning strategy simulates the situation where data is being predicted outside an area of higher coverage.

Model accuracy of different partitioning methods

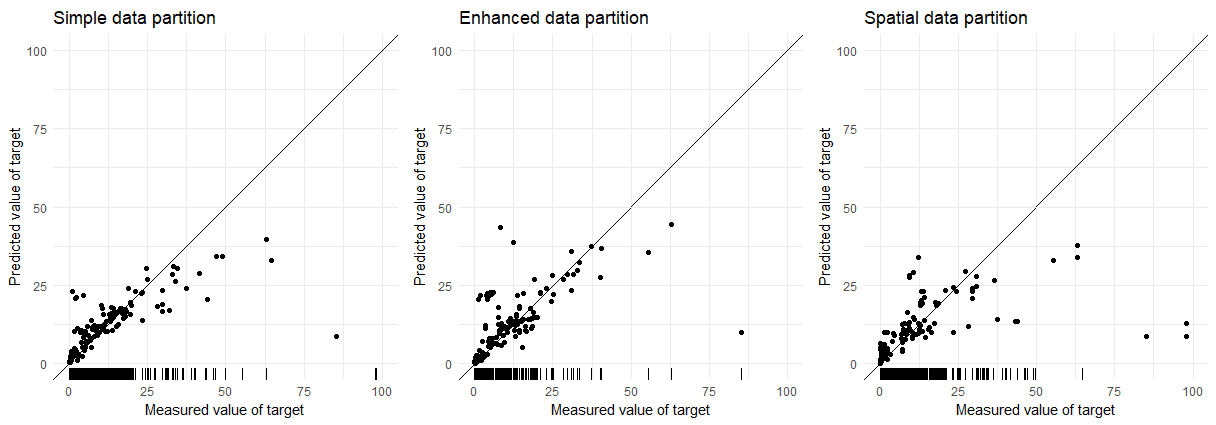

To compare the accuracy of the three different partitioning methods I used a random forest model composed of 500 trees. These models are just built on the geochemical constraints and don’t incorporate spatial locations. The exact model or parameters don’t matter as much here; the change in error/accuracy is the important part. The plots below compare of measured values and predicted values of the target variable for the three partitioning techniques. The ticks along the x-axis display the coverage of the target variable in the training data.

| Partition | Test MAE | Test RMSE |

|---|---|---|

| Simple | 23.16 | 47.71 |

| Enhanced | 29.53 | 52.36 |

| Spatial | 34.50 | 76.39 |

There is a large increase in error between the Simple and Spatial partitioning (~50% increase). In the future I may update this blog post with a more robust exploration of these models over multiple random splits to better estimate their accuracy.

How Difficult Should Development or Cross-Validation Tests Be?

As there is a huge large difference in accuracy between the three models, this may bring up the question “how difficult should these tests be when trying to develop a prediction pipeline?” I think a better question is how realistic is the test. In the case here, a potential data leak was identified (i.e., multiple records per well), but then a more realistic test was created by spatially clustering the data. Using more realistic tests may cause model accuracy to suffer but overall the results might be more informative. Additionally, more generalized models may excel in these sorts of scenarios (e.g., spatial hold out).

Role of exploratory data analysis in test design

Through this process I learned that exploratory data analysis (EDA) also plays a huge role in this aspect of machine learning. I had originally viewed EDA as the focus during data cleaning and finding relationships to model. However, time spend in EDA allows you to unravel the heterogeneities in the dataset to see how balanced features will be when split into training and testing datasets. Additionally, EDA also can be expanded beyond the training dataset, into the the dataset that the model will be deployed to. This this allows one to again see how features are spread between the two, and provide some insight into how well models will perform once deployed.

TL;DR - Evaluating Model Design

Prediction is becoming a huge business in geoscience. Companies are pouring resources into developing techniques for predicting mineral targets or subsurface reservoir properties. As shown here, the accuracy of these tests can be influenced by how datasets are divided for model building. This kind of information isn’t always communicated to the people contracting this kind of work, likely due to the very technical nature of the topic. In short, the division of training and testing should mimic the deployment scenario: are models being used to interpolate between data points, or is data being used to extrapolate outside of the dataset, and there are numerous other scenarios that could be used as well.

Understanding the impact of partitioning methods is important for any machine learning work, but is very important for neural network models used for mineral and hydrocarbon exploration. In these scenarios training data can be very sparse or located in centralized regions (i.e., data is centralized in prospective areas). Deciding how to split the data into training and testing would be very difficult depending on the spatial coverage - I’ve never done it. There is no clear-cut way to do it, but understanding the impacts of these strategies and how they may influence predictions is important.